By Deana Soper Pinkelman, PhD

Do any of the following statements sound familiar?

“You need to rest, so you should supplement with formula.”

“Your baby has jaundice, so you should supplement with formula.”

“Your milk hasn’t come in yet, so you need to feed formula.”

Some new parents are under the impression that milk produced in the first few days is not enough to meet the needs of the newborn and come to the conclusion that the baby needs to be supplemented with formula “until the milk comes in.” While there are medical conditions that might prevent the production of sufficient milk, these conditions are relatively rare. Breast cells are able to produce milk by the beginning of the third trimester of pregnancy.2 This means that milk can be expressed prior to giving birth, which is referred to as antenatal milk expression. Antenatal milk expression can be very helpful, particularly for individuals who suspect that their infant could experience low blood sugar levels due to conditions such as gestational diabetes. For more information on antenatal milk expression, see Expressing Milk Before Birth: A Tool for Use in Special Circumstances.

At birth, a drop in estrogen and progesterone allows the high prolactin (a hormone that is released during pregnancy and nipple stimulation) levels to give a signal to the breasts to secrete a dense concentrated milk called colostrum, also referred to as “early milk.” It is very important for the baby to receive colostrum early and often. Colostrum is a thick, sticky, yellow milk that is high in antibodies and protein. It also serves as a laxative to help stimulate the passing of meconium, which is a dark, sticky substance that lines the intestines of the infant.

Parents of babies who develop significant jaundice (high bilirubin levels) may be told that they must feed the infant formula to treat the condition. Jaundice is usually identified when there is a yellowing of the skin and white portions of the eyes. It can be the result of different physiologic sources, but it results from a buildup of a substance called bilirubin. Bilirubin is usually broken down and excreted, but sometimes the infant’s system has difficulty performing this function. Because meconium is sticky, it tends to enable the reabsorption of bilirubin back into the baby’s body. Thus, getting rid of meconium faster will help bilirubin levels to drop. This means that breastfeeding early and often will help because of colostrum’s laxative effect. More information on breastfeeding and jaundice can be found here.3

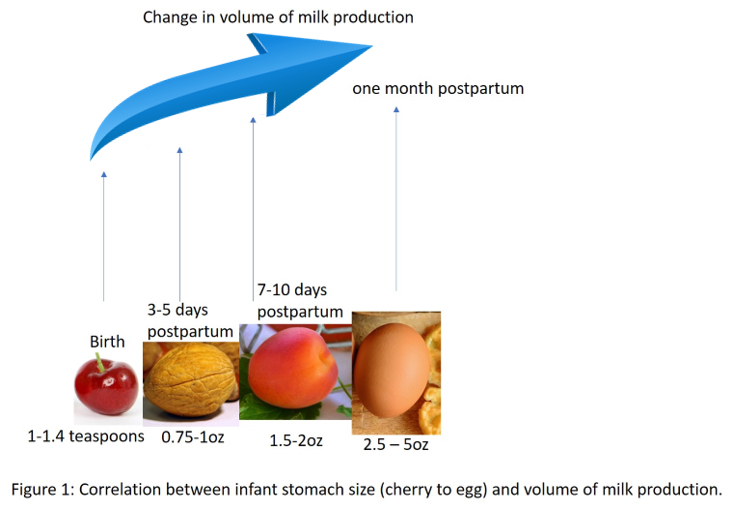

One of the many important roles of colostrum is to protect the infant from the abundant microbes in the outside world. Antibodies and white blood cells present in colostrum serve as immunological protection as the infant is exposed to germs. Approximately 2 – 5 days postpartum, the colostrum begins to transition to mature milk. The breasts have increased blood supply and gradually produce more milk. By approximately 8 – 10 days, the mature milk has been established and will continue to be maintained by breastfeeding or expressing milk. Many people think of this as a switch, but milk production should be thought of as being on a continuum. The body produces what the baby needs when they need it. At birth, the infant has a small stomach and requires a high level of calories and protein, which is exactly what is produced immediately postpartum. As the newborn develops nutritional, as well as volumetric needs, continue to increase. Because this is a transitional process and not a switch, the commonly used phrase “milk coming in” is technically inappropriate. The answer to the question of “When will my milk come in?” is during pregnancy.

Feeding the infant early and often not only is helpful for infant nutrition, digestion, and immunologic protection, but it also assists in establishing milk production long-term. Research has indicated that how frequent one nurses or pumps in the first few days has an impact on long-term milk production.1

My baby cries after feedings. What now?

If an infant cries right after ending the feed, parents might think that their baby is still hungry. This may or may not be the case. If the infant ends the feed (usually by unlatching from the breast or pulling away from the bottle, if bottle-fed) and is crying, comfort the infant and try nursing again. Parents might try to relatch the infant on the other breast, rock the baby, place the baby on a parent’s or caregiver’s chest, gently bounce the baby, or use white noise to calm the baby. For more information on fussiness in babies, see this article Why Is Your Baby Fussing?.5 If this happens frequently and the infant cannot be consoled, it could be cause for investigation with the help of a Breastfeeding USA Counselor, lactation consultant (IBCLC), or health care professional to find the root cause of the problem. They can help the parents with tracking infant development, transition from meconium to a yellow-seedy stool, the number of wet and stool-filled diapers, as well as infant weight gain, which would also be helpful in determining if the infant is breastfeeding effectively.4

Finally, if you have any concerns or questions postpartum, reach out for help early and often. Support can come in the form of attendance at breastfeeding support groups or making an appointment for a private consultation with a lactation consultant (IBCLC) or a breastfeeding peer counselor. It is commonly thought that because breastfeeding has been practiced for thousands of years it should be easy, but sometimes there are challenges. Many women need help, including myself. After the birth of my second child and already a Breastfeeding Counselor with Breastfeeding USA, I reached out to my fellow counselors for help and to a trusted International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC). You are not alone, and we are here to help!

References

- Daly, S.E.J. and Hartmann, P.E. 1995. Infant demand and milk supply. Part 1: Infant demand and milk production in lactating women. Journal of Human Lactation. 11:21-26.

- Lauwers, J. and Swisher, A. 2011. Counseling the Nursing Mother A Lactation Consultant’s Guide. 5th ed. Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. Sudbury, MA.

- La Leche League Canada. “Jaundice and Breastfeeding.” https://www.lllc.ca/jaundice-and-breastfeeding

- Mohrbacher, Nancy. “Diaper Output and Milk Intake in the Early Weeks.” https://breastfeedingusa.org/diaper-output-and-milk-intake-in-the-early-weeks

- Fulara, Elise. “Why is Your Baby Fussing?” https://breastfeedingusa.org/why-is-your-baby-fussing

Other Helpful Resources

- Bonyata, Kelly. “How Does Milk Production Work?” https://kellymom.com/hot-topics/milkproduction/

- Neville, Margaret. “Lactogenesis: The Transition from Pregnancy to Lactation.”

http://www.pediatric.theclinics.com/article/S0031-3955(05)70284-4/references

- Mohrbacher, Nancy. “Diaper Output and Milk Intake in the Early Weeks.”

https://breastfeedingusa.org/diaper-output-and-milk-intake-in-the-early-weeks - “Breast Milk Production.” https://www.sutterhealth.org/health/breast-milk-production

- Expressing Milk Before Birth: A Tool for Use in Special Circumstances. https://breastfeedingusa.org/expressing-milk-before-birth-a-tool-for-use-in-special-circumstances/

Deana Soper Pinkelman, PhD

Deanna M. Soper, Ph.D. is a Breastfeeding USA Counselor coordinating the Cross Timbers Chapter in Flower Mound, TX. She is an assistant professor of biology at the University of Dallas and is a mom of two children who nursed both until 2 – 2.5 years old.

© Breastfeeding USA 2019, all rights are reserved.